SLB member Myles Klynhout reflects on the January teacher training workshop at the coop.

Firstly, a huge thankyou to James Venner & Neil McMillan for co-running the pronunciation workshop. Also, special thanks to Laura and Gerry for hosting the Calçotada that followed in the afternoon. I feel the session did a magnificent job of bridging the gap between SLA research and classroom practice. A bountiful number of well-presented ideas. I couldn’t type fast enough on the i-pad and resorted to sketching flowcharts and diagrams on paper instead. Here are just 3 of many points I walked away with to take into the classroom:

1. Intelligibility vs. Accentedness

I was intrigued by this first point and spurred on to go home and do a little more reading. I found that many studies online suggest that although strength of foreign accent is correlated with perceived comprehensibility and intelligibility, a strong foreign accent does not necessarily reduce the comprehensibility or intelligibility of L2 speech. As James highlighted:

A foreign accent won’t necessarily make a speaker hard to understand. As language teachers we must identify the aspects of a learner’s speech that could lead to a breakdown in communication, including mispronunciation of specific phonemes, as well as issues with word-stress, rhythm and speed.

However, that is not to say just because we understand a student’s pronunciation, other listeners will, too! As teachers in a foreign country we are most likely attuned to the sounds of the learner’s language and we are, therefore, more ‘sympathetic listeners’. We need to be sure we are not letting errors in specific phonemes, word-stress, etc. slip into the abyss. Drawing the students attention to potential issues is an essential part of error correction. More on this to be discussed in point number 3.

2. Importance of Input

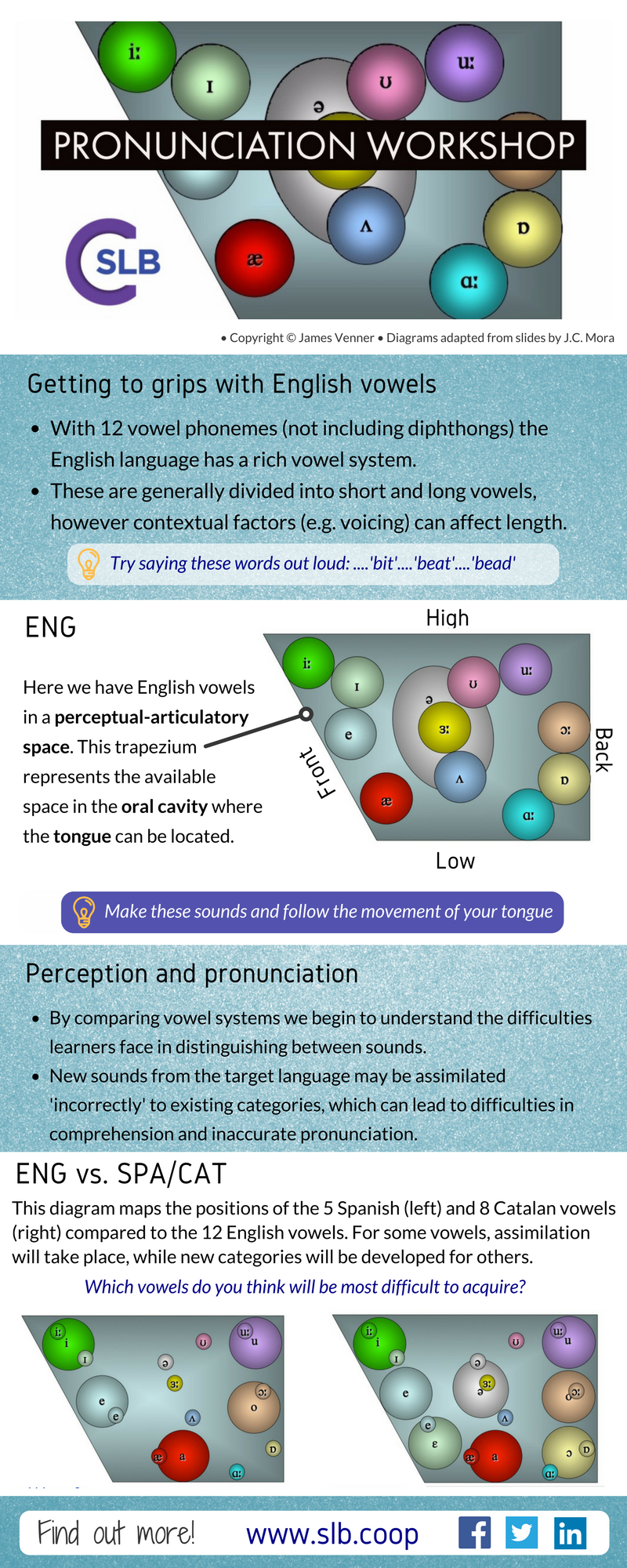

Pronunciation is not only about what the students can produce. If our students are experiencing difficulty distinguishing sounds when listening, how can we expect them to produce these distinct sounds accurately? Learners will often assimilate new sounds from the target language incorrectly to match existing sounds in their L1 (see info-graphic below), leading to difficulties in both perception and pronunciation. The number of times I have had a student tell me something along the lines of ‘I understand you (and your Australian accent) perfectly, but at work, I really struggle to understand my boss (from Switzerland).’ As James explained:

The development of new phonetic categories is aided by exposure to high variability input. We should never limit our learners by providing them with a single speech model, our own voices; rather, we should challenge them to process a range of models, in line with their real-life needs.

Later in the session Neil highlighted that as teachers we should use our accent as a guide, but not impose it (or RP) as a model. Nowadays, with technology readily at our fingertips and a vast amount of video content from all over the world available online, it is evermore easier for the teacher to bring a range of native and non-native English accents into the classroom. Which accents to focus on would need to be determined during the needs analysis. Which raises the question, how many needs analyses do you see that thoroughly assess the accents students will need to deal with outside the classroom?

3. Integrating pronunciation into tasks and activities

I have often questioned the value and time-efficiency of teaching a full lesson on one pronunciation item, e.g. the difference between Ship and Sheep. I was pleased to hear that others in the room felt the same. Neil first established that the learning trajectory of pronunciation in adults is non-linear, and that when teaching pronunciation via a ‘PPP’ model or in isolation, meaning is bypassed – the very heart of perceptual awareness problems associated with pronunciation errors.

Intensive pronunciation courses aim to diagnose perceptual problems and direct the learner to focused, isolated practice, Whereas a meaning- and process-based approach (comm., TBL) can address perceptual issues at root – pronunciation work is integrated.

We then set off to look at practical ways of providing error correction in the classroom during a task or activity: raising students perceptual awareness, input, feedback, self-monitoring, instruction can all have an influence. Each group was presented with three scenarios in a classroom of learners, whose L1 was Spanish, where we would need to determine a possible error in pronunciation and how we would attend to it re-actively. Here is what we came up with:

Wrapping your tongue (and mouth) around it – ‘mouth training’.

“In eschool in espain I estudied espanish” after considerable thought, and a nudge in the right direction from James, we realised that this could be attended to with some quick ‘mouth training’. Having the students hold their hands on their cheeks and touching the corner of their mouths would allow them to feel the movement of their jaw when they produced the word correctly vs. incorrectly.

I was then introduced to the art of ‘back-chaining drills’. My word to teach – flabbergasting!

repeat after me:

ting…

gas ting…

bber gas ting…

“flabbergasting!”

This could also be done with chunks of language starting from the mid-point of a phrase called ‘in-chaining drills’.

repeat after me:

laɪ…

dʒəlaɪ…

ʊdʒəlaɪ…

“Would you like ….”

(The idea is that you build up the sounds independently of the whole words in the phrase so that the phrase is only revealed at the end – in this way the focus is purely on sound)

Interested in attending one of our ELT workshops?

Our next workshop will be led by Dr. Geoff Jordan this month.

Ttile: ‘Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT): From Needs Analysis to Task Design’

Date: Saturday, 25th February 2017

City: Barcelona

Please email me at myles@slb.coop for more information and ticketing.